Who is this blog for?

Business and technology leaders gathered on 16th April 2024, at the Babble-hosted Fit to Lead Executive Lunch and Forum. Held at the prestigious Buffini Chao Deck in London’s National Theatre, the event featured a lineup of prominent speakers with the Director of Quirk Solutions and longtime friend to Babble, Chris Paton, hosting both panel sessions. The esteemed panellists shared many insights about leading in the face of adversity and deeply explored the first two pillars of the Fit to Lead framework. This framework equips modern leaders with the mental, physical, and ethical edge to thrive in today’s demanding landscape.

Reading time: 9 minutes

In the previous blog, we took a deep dive into the mindfulness techniques the Room to Breathe panellists shared to navigate the challenges faced by the modern leader. In light of the physical and mental fitness pillars of the Fit to Lead framework, Chris Paton (CP), Dr. Steve Ingham (SI), Orla Chennaoui (OC), Sarah Furness (SF) and Mike Bates (MB) unpacked the mind-body connection in practice. From memento mori mortality meditations to breathwork exercises synced to your favourite songs, all of the techniques discussed were centred around helping you become a more resilient leader.

While the tools shared were nothing short of powerful, they are largely used to manage stress and anxiety – not prevent it. This led Chris to start a discussion with the panellists about the things that we can’t control. More specifically, the line of questioning below leads to impactful leadership insights regarding pivoting when things go wrong; overcoming the fear tied to big challenges and how to set goals effectively to lead with intent.

As such, Chris began this part of the conversation by asking the panellists what happens when things go wrong:

“Tell us a little bit about a time when something didn’t go according to plan and what your reaction to it was?”

SF: “Leadership is actually what we do when things go wrong. What I learned in the Air Force is nobody gets out of bed to crash a helicopter. Every single person wants to do a great job. So if they’ve made a mistake, anyone else could have made a mistake. So what is important is what we do with the mistake. And no matter how much of a good game we talk about this, it is really uncomfortable admitting when you’ve [made a mistake]. You will feel ashamed, [or] you might be scared of what’s going to happen to you.

This leads into [workplace culture: firstly, you’ve got to be brave enough to] take ownership, which is scarier than it sounds. Then you’ve got to share it with the assumption that ‘if I made this mistake, so could they’. I now have a professional duty to share this learning so that other people can benefit from it. The second-order effect of that is creating a culture where people do feel empowered to speak up and you’re accelerating the learning and growth. So, it’s got our connotations for performance, culture, [and] resilience because a lot of resilience is about bounce back ability.”

OC: “[Taking ownership of mistakes at work] takes a lot of trust in your culture. [It’s about] having that ability to trust the culture that you can make a mistake, admit you’ve made the mistake and that others will understand they could be in that position as well. If you live or work in a fear [and blame] culture, it’s the exact opposite: everyone then is trying to cover up and blame somebody else, which nobody learns from.”

OC: “[Taking ownership of mistakes at work] takes a lot of trust in your culture. [It’s about] having that ability to trust the culture that you can make a mistake, admit you’ve made the mistake and that others will understand they could be in that position as well. If you live or work in a fear [and blame] culture, it’s the exact opposite: everyone then is trying to cover up and blame somebody else, which nobody learns from.”

MB: “It’s the power of the ‘hot debrief’: We [in the military] used it when we were running covert operations – [the] UK Special Forces [still] use it. [At] the end of every single mission, you quickly get together and you say, ‘Okay, warts and all, how did it go? What did we do well? What [didn’t] we do very well? And perhaps it was you or it was me.’

[When] those people put their hands up, you start to build that culture of trust. That’s vitally important because you don’t know in your business who’s going to have the next best idea. That moves you from where you are now to where you want to be. I’ll tell you now, they will not put their hand up with that idea unless they feel like they’re trusted and part of a community.

I think the question I get asked the most in business is, ‘How are you going to deal with the unforeseen when the wind’s different or the helicopter’s not reacting the same or there’s a new acquisition that’s not quite to plan?’ The truth is you don’t know how you’re going to cope. You don’t know if you’re capable half the time. But if you’ve built a wall of evidence, you’re constantly putting yourself in positions to challenge yourself. You build a wall which is like a fortress of self-belief and you can deal with anything.

CP: “Absolutely. Just picking up on that piece around mistakes and creating that psychologically safe space. [What makes the hot debrief so powerful] is the leader should always go first. So you sit there as the person who is running that team and you go, ‘This is my part in what happened. Here’s how I saw it. Here’s where I think I could do better.’ [This] essentially [creates] the space for others to contribute.”

Difficult conditions intensify the need for fitter leaders. Yet having to respond to the challenges – and opportunities – of an unstable economic and political climate makes it harder to prioritise the pillars of leadership fitness. However, the majority (72%) of business leaders surveyed in our Fit to Lead report take on demanding physical challenges to help build their leadership perseverance – and this is what led Chris to ask the following question:

“Why is it that some people find it easier to [take on a big challenge] than [remaining engaged in ongoing daily tasks]?

MB: “For me, it’s dragging yourself into deep waters and seeing if you can swim. It’s finding where your edges are. I think that’s really important. In business, you’re going to have to perform every single day. It’s the constant showing up that is the key. That’s why leaders tend to move towards things like Ride Across Britain, because it’s a bigger, more protracted challenge, and it mimics business a bit more closely.”

Chris then asked the audience how many of them actively seek to ‘find their edges’ by purposely getting out of their comfort zones with a big challenge. By a show of hands, it was found that the majority of the attendees preferred the ongoing daily tasks of their jobs. He then asked Sarah what her thoughts were on that:

SF: “With a challenge, you’ve got an obvious goal, [whereas] when it’s a daily thing, it’s just harder to connect to why [you’re] doing it. It’s easier to connect to the why when you’ve got a big challenge.”

MB: “[It’s important to remember that in taking on a big challenge] motivation will shift. You have to accept that.”

OC: “The beauty of committing to something huge is if you don’t do it, you’ve still done more training than you would have done if you’d never signed up for it in the first place. What’s really beautiful about achieving a challenge is the confidence it gives you right across your life. [These big challenges] teach you so much about yourself that you don’t even realise that you have to discover before you do it.”

The conversation turned to effective goal setting and the power of intention – with journaling emerging as another powerful tool.

SI: “There is some good evidence that delivering on any goal can spill over and improve your ability to deliver other goals. That can be completely unrelated, whether it’s learning a language or growing some vegetables that can improve your ability to set a goal and work toward it.

But the interesting thing that’s evolved over the last five to 10 years or so is how we set goals and the effectiveness of those goals. There are largely two main types of goals: the big goal [like getting an Olympic gold medal], and the other one is a proximal goal. They have to go hand in hand, but they are what’s called specific goals: ‘I want to achieve that. I’ve got to deliver this”.

But the interesting thing that’s evolved over the last five to 10 years or so is how we set goals and the effectiveness of those goals. There are largely two main types of goals: the big goal [like getting an Olympic gold medal], and the other one is a proximal goal. They have to go hand in hand, but they are what’s called specific goals: ‘I want to achieve that. I’ve got to deliver this”.

The other one that seems to be emerging, [amongst champions are] open goals, also known as ‘vague goals’. [An example would be] ‘I wanted to try my best’ or ‘I wanted to develop consistency’. So they’re much more nebulous, [and about] just trying and [noting what you did and didn’t manage to achieve that day. These goals allow you to start without trying to take on too much at once which would lead to failure].”

CP: “This plays to a concept that the military has called ‘intent’: where we will literally say ‘we intend to’. We deliberately choose that verb because that allows us the flexibility to not do the thing that’s been stated. We used intent all the way down through the organisation to allow that latitude of, ‘We’re going to adapt because we’ve got a space to be able to work within’.

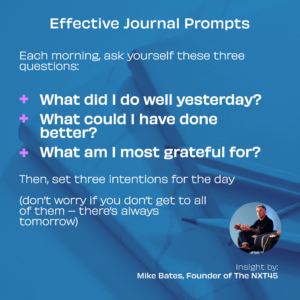

MB: “[Journaling is] something I’ve been starting to do this year, and [being more intentional is] one of the reasons [why]. It’s really important to organise your thoughts and just get out of your head for a minute and write down how you really feel. [This is what makes journaling such a] powerful tool.”

SI: “If people are interested in improving their performance, they would be journaling. They would be freeing up their cognitive space. They would be investing in sleep, exercise, [and] good nutrition. You would be doing this if you want to execute outstanding cognitive decision-making performance in your business in the same way that you would want a long jumper to hit the board and fly. You would prioritise certain things. So it’s not a case of, this is nice for the sake of it. No, that will improve the way you operate.”

OC: “As you say, if you were thinking about really performing the best that you can in business, you’d be prioritising exercise and sleep – and you can measure all of these things. [There are so many ways in which you can measure within minutes, the physiological improvement of walking, for example. This [leaves] almost no excuse to not implement these simple, cheap, quick, [and] free things to do that improve every aspect of our life and business.”

From Fear to Focus: Sharpen Your Leadership Edge

Leaders aren’t born fearless, and none of us are without fault. Taking ownership of mistakes isn’t just damage control – it’s a foundation for leaders to build trust in their organisations. By stepping up to challenges and learning from setbacks, you build confidence and uncover your true capabilities. Journaling fuels this growth, empowering you to make sharp, strategic decisions. So, embrace discomfort, conquer your fears, and become Fit to Lead.